dichotomy of assumptions

Published 2024-03-03T01:45:00.003Z by Physics Derivation Graph

In Physics there are some assumptions that form a dichotomy:

is the speed of light constant or variable? is the measure of energy discrete or continuous?

In the dichotomy of assumptions, one of the two assumptions is reflective of reality, and the other is an oversimplification. The oversimplification is related to reality by assumptions, constraints, and limits.

(I define "oversimplification" as the extension of useful assumptions to incorrect regions.)

Another case where oversimplification is the link between domains is quantum physics and (classical) statistical physics. Quantum particles are either Fermions (odd half integer spin) or Bosons (integer spin), but that is practically irrelevant for large ensembles of particles at room temperature. The aspects that get measured at one scale (e.g., particle velocity) are related to but separate from metrics at another scale (e.g, temperature, entropy). Mathematically this transition manifests as the switch from summation to integration.

So what?

What boundaries should the Physics Derivation Graph transgress? What oversimplifications are adjacent?

The evidences of dissonance (e.g, Mercury’s perihelion based on Newtonian gravitation versus relativity, the Deflection of Starlight; source ) are not relevant for bridging domains. They are illustrations of the oversimplification.

Update 2024-03-10 : on the page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phase_space#Quantum_mechanics

"by expressing quantum mechanics in phase space (the same ambit as for classical mechanics), the Weyl map facilitates recognition of quantum mechanics as a deformation (generalization) of classical mechanics, with deformation parameter ħ/S, where S is the action of the relevant process. (Other familiar deformations in physics involve the deformation of classical Newtonian into relativistic mechanics, with deformation parameter v/c; or the deformation of Newtonian gravity into general relativity, with deformation parameter Schwarzschild radius/characteristic dimension.)

See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wigner%E2%80%93Weyl_transform#Deformation_quantization

prompt

In Physics there are dichotomies of assumptions like

is the speed of light constant or variable?

is the measure of energy discrete or continuous?

One of the two assumptions is reflective of reality and the other is an oversimplification. The oversimplification is related to reality by assumptions, constraints, and limits.

What are other examples of these dichotomies in Physics?

Using https://aistudio.google.com/prompts

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: thoughts

Here's a thinking process to arrive at the list of physics dichotomies:

Understand the Core Request: The request asks for pairs of opposing assumptions in physics, where one is a simpler, often historically earlier, model and the other is a more nuanced, "real" (or currently accepted as more accurate) version. The key is identifying the simplification and how it's related to the more accurate model.

Brainstorm Broad Areas of Physics: To generate diverse examples, think about the major branches of physics:

Classical Mechanics (motion, forces)

Electromagnetism (light, fields)

Thermodynamics (heat, energy)

Quantum Mechanics (atoms, subatomic particles)

Relativity (space, time, gravity)

Consider Key Concepts Within Each Area: For each area, brainstorm core concepts and how they are described at different levels of approximation.

**Classical Mechanics:** Think about how objects are treated – point masses vs. extended bodies, rigid vs. deformable. Consider forces – are they always instantaneous? What about friction and energy loss?

**Electromagnetism:** The prompt itself gives a great example (constant vs. variable speed of light, which links to the wave/particle duality). Think about the nature of electric and magnetic fields – discrete charges or continuous distributions?

**Thermodynamics:** What about the nature of matter? Is it perfectly divisible or are there ultimate particles? Is heat a fluid (caloric theory) or the motion of particles?

**Quantum Mechanics:** This field is rich with dichotomies. Think about the nature of particles – are they particles or waves? Are their properties definite before measurement? Is information conserved?

**Relativity:** The prompt's example of the speed of light falls here. Think about space and time – are they absolute or relative? Is spacetime flat or curved?

Formulate Dichotomies: For each brainstormed concept, try to form a clear "either/or" statement representing the simplification and the more accurate model.

*Example (Classical Mechanics):* Point mass vs. Extended Body. The point mass assumption simplifies calculations but doesn't capture rotational motion or internal structure.

*Example (Electromagnetism):* Light as a Wave vs. Light as a Particle. The wave model explained diffraction, but the particle model explained the photoelectric effect. Now we have wave-particle duality.

*Example (Quantum Mechanics):* Deterministic Trajectories vs. Probabilistic Descriptions. Classical physics assumes we can know both position and momentum perfectly. Quantum mechanics introduces uncertainty.

Refine and Add Details: Once you have a list of dichotomies, add details explaining:

Which is the simplification.

How the simplification is useful (e.g., for easier calculations).

The assumptions, constraints, and limits under which the simplification holds.

How the more accurate model relates to the simplification.

Organize and Categorize: Group similar dichotomies together for better readability and flow. Using the broad areas of physics as categories works well.

Review and Expand: Read through the list. Are there any obvious omissions? Can any of the explanations be clearer? Consider adding a brief introductory and concluding paragraph to frame the discussion. For example, explicitly mentioning the historical progression of these ideas can be valuable.

**Self-Correction Example during the process:**

Initial thought: "Classical vs. Quantum" as a dichotomy.Correction: While a valid broad distinction, it's too general for the specific prompt. The prompt asks for *specific assumptions*. Refine this to find more concrete examples *within* the transition from classical to quantum, like the deterministic vs. probabilistic nature of particle paths.

By following these steps, and iterating through brainstorming and refinement, you can generate a comprehensive and well-explained list of physics dichotomies like the example provided in the initial prompt.

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: response

You've hit upon a fascinating aspect of how physics progresses! Many of our foundational concepts started as convenient simplifications that, upon closer examination and with more advanced tools, revealed themselves to be more nuanced. Here are some other examples of such dichotomies in physics:

**Mechanics & Motion:**

**Point Particle vs. Extended Body:**

**Simplification (Point Particle):** Treating an object as having mass but no spatial extent. This is incredibly useful for analyzing translational motion, especially over large distances or when internal structure isn't relevant.

**Reality (Extended Body):** Real objects have size, shape, and internal structure. This leads to considerations of rotation, deformation, and internal energy. The point particle assumption breaks down when these factors become significant (e.g., analyzing the tumbling of a satellite or the collision of two galaxies).

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** Valid when the size of the object is much smaller than the distances involved or when internal motion isn't a primary concern.

**Rigid Body vs. Deformable Body:**

**Simplification (Rigid Body):** Assuming an object maintains its shape and size regardless of applied forces. This simplifies the analysis of rotations and collisions.

**Reality (Deformable Body):** Real objects can change shape under stress. This leads to the study of elasticity, plasticity, and fluid dynamics. The rigid body assumption breaks down when considering stresses, strains, vibrations, or fluid flow.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** Useful for objects where deformation is negligible under the forces involved or for short timescales before significant deformation occurs.

**Instantaneous Force vs. Force Acting Over Time:**

**Simplification (Instantaneous Force - Impulse):** Treating a force as acting for an infinitesimally short time, resulting in an instantaneous change in momentum (impulse). Useful for analyzing collisions.

**Reality (Force Acting Over Time):** Forces always act over a duration, however short. This leads to the concepts of work and energy transfer. The impulse approximation breaks down when the duration of the force becomes relevant to the dynamics.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** Useful for quick impacts where the interaction time is much shorter than other relevant timescales.

**Electromagnetism:**

**Discrete Charges vs. Continuous Charge Distribution:**

**Simplification (Discrete Charges):** Treating electric charge as being carried by individual particles (electrons, protons). Useful for understanding fundamental interactions.

**Reality (Continuous Charge Distribution):** Often, for macroscopic objects or dense plasmas, it's more convenient to describe charge as a continuous distribution with a charge density. This simplifies calculations involving large numbers of charges. The discrete charge approach becomes cumbersome with vast numbers of particles.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** The continuous approximation is valid when considering regions much larger than the spacing between individual charges.

**Ideal Conductor vs. Real Conductor:**

**Simplification (Ideal Conductor):** Assuming zero electrical resistance, meaning current flows without any energy loss. Useful for circuit analysis at a basic level.

**Reality (Real Conductor):** All materials have some resistance, leading to energy dissipation as heat (Joule heating). This is crucial for understanding efficiency and heat management in electrical systems.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** The ideal conductor assumption is valid when resistance is negligibly small compared to other components in the circuit.

**Thermodynamics & Statistical Mechanics:**

**Isolated System vs. Open/Closed System:**

**Simplification (Isolated System):** No exchange of energy or matter with the surroundings. Useful for theoretical calculations and understanding fundamental thermodynamic principles.

**Reality (Open/Closed Systems):** Real systems interact with their environment. Open systems exchange both energy and matter, while closed systems exchange energy but not matter. Understanding these interactions is crucial for real-world applications.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** The isolated system is an approximation, useful for short timescales or when interactions with the surroundings are minimal.

**Reversible Process vs. Irreversible Process:**

**Simplification (Reversible Process):** A hypothetical process that can be reversed without any net change in the system or its surroundings. Useful for defining thermodynamic equilibrium and maximum efficiency.

**Reality (Irreversible Process):** All real-world processes are irreversible due to factors like friction, heat transfer through a temperature difference, and mixing. Understanding irreversibility is key to analyzing the limitations of engines and other thermodynamic systems.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** The reversible process is a theoretical idealization. Real processes can approach reversibility under specific conditions (e.g., slow, quasi-static processes).

**Quantum Mechanics:**

**Deterministic Trajectories vs. Probabilistic Descriptions:**

**Simplification (Deterministic Trajectories - Classical Intuition):** The idea that if you know the initial position and momentum of a particle, you can predict its future path with certainty.

**Reality (Probabilistic Descriptions):** In quantum mechanics, particles don't have definite trajectories. Their behavior is described by probability waves, and we can only predict the probability of finding a particle in a certain location or with a certain momentum.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** The deterministic view works well for macroscopic objects where quantum effects are negligible. At the atomic and subatomic level, the probabilistic nature is fundamental.

**Particles with Definite Properties vs. Superposition of States:**

**Simplification (Definite Properties - Classical Intuition):** The idea that a particle has a single, definite value for properties like position, momentum, and spin at any given time.

**Reality (Superposition of States):** Quantum particles can exist in a superposition of multiple states simultaneously until a measurement is made. For example, an electron can be in a superposition of spin-up and spin-down states.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** The definite property view is a good approximation for classical objects. Superposition is a purely quantum phenomenon.

**Relativity:**

**Flat Spacetime vs. Curved Spacetime:**

**Simplification (Flat Spacetime - Newtonian Physics & Special Relativity):** Treating spacetime as a flat, unchanging background where events occur. Useful for describing motion at non-relativistic speeds in the absence of strong gravity.

**Reality (Curved Spacetime - General Relativity):** Mass and energy warp spacetime, causing gravity. This curvature affects the motion of objects and even light.

**Assumptions/Constraints/Limits:** Flat spacetime is a good approximation when gravitational fields are weak and speeds are much less than the speed of light.

These are just a few examples, and the lines between the "simplification" and "reality" can sometimes be blurry and depend on the specific context and the level of precision required. Physics progresses by refining these simplifications, understanding their limitations, and developing more accurate models that incorporate the complexities of reality. This process often involves the introduction of new concepts, mathematical tools, and experimental techniques.

prompt

Are there examples of Derivations of Mathematical Physics which span these assumptions?

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: thoughts

Here's a breakdown of the thinking process to generate examples of derivations spanning those dichotomies:

**Understand the Core Request:** The user wants examples of *mathematical derivations* in physics where we start with a simplified assumption and then refine it to incorporate the more "realistic" scenario. This means the derivation should show how the simplified case relates to the more complex one.

**Review Previous Examples:** Look back at the dichotomies listed previously. These are the starting points for the derivations.

**Choose Dichotomies Suitable for Derivations:** Not all dichotomies lend themselves equally well to explicit mathematical derivations. Focus on those where a clear mathematical bridge exists between the simplified and complex cases. For example, "isolated vs. open system" is a concept, but deriving the thermodynamics of an open system *from* an isolated one is less direct than, say, going from a point particle to a rigid body.

**Select Specific Examples within Chosen Dichotomies:** For each suitable dichotomy, think of a concrete physical scenario that exemplifies it and allows for a mathematical treatment.

**Outline the "Simplified" Derivation:** Describe the mathematical steps involved in the simplified case. This should be a standard result in introductory physics. Focus on the key assumptions being made.

**Outline the "More Realistic" Derivation:** Describe how the derivation changes when the simplifying assumption is relaxed. Highlight the new terms or concepts that need to be introduced. Crucially, *show how the simplified result is recovered as a limit or special case of the more realistic one.* This is the core of the "spanning" aspect.

**Emphasize the Bridging Elements:** Point out the mathematical connections between the two derivations. This could involve:

Taking a limit (e.g., size approaching zero).

Setting a parameter to zero (e.g., resistance).

Integrating over a continuous distribution to represent the discrete case.

Introducing additional terms or degrees of freedom.

**Provide Concrete Examples:** Use specific equations and mathematical expressions to illustrate the derivations. This makes the explanation much clearer.

**Consider Different Areas of Physics:** Aim for examples across mechanics, electromagnetism, and potentially other areas to show the broad applicability of this concept.

**Structure for Clarity:** Organize the examples logically, clearly labeling the simplified and more realistic derivations and the bridging elements. Use bullet points and clear language.

**Self-Correction/Refinement During the Process:**

**Initial thought:** "Can I derive the Navier-Stokes equations from the ideal gas law?" **Correction:** While related, it's not a direct derivation spanning the "discrete vs. continuous" dichotomy in the same way as the charge example. Focus on clearer, more direct mathematical links.

**Initial thought:** "Should I include quantum mechanics?" **Correction:** While superposition is a good example of the dichotomy, showing a direct mathematical *derivation* from the "definite property" case is more subtle and might require advanced quantum field theory. Stick to more elementary examples for clarity.

**Focus on the "derivation" aspect:** Make sure the examples genuinely show a mathematical path from the simplified to the complex, not just a conceptual comparison.

By following these steps and refining the examples, the goal is to produce a clear and illustrative answer that directly addresses the user's question.

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: response

Yes, absolutely! There are many examples where derivations in mathematical physics start with a simplified assumption and are then extended to incorporate the more realistic scenario, showing how the simplification arises as a special case. Here are some examples tied to the dichotomies we discussed:

Point Particle to Extended Body (Mechanics):

Simplified Derivation (Point Particle):

Newton's Second Law for a Point Particle: F = ma, where F is the net force, m is the mass, and a is the acceleration of the single point representing the object.Analysis of Motion: Solving differential equations based on this law gives the trajectory of the point particle.

More Realistic Derivation (Extended Body - Rigid Body):

Newton's Second Law for the Center of Mass: The center of mass of the extended body moves according to Fext = Macm , where Fext is the net external force and M is the total mass. This is essentially the point particle equation applied to the center of mass.Torque and Rotational Motion: Introduces the concept of torque (τ) and moment of inertia (I) to describe rotational motion: τ = Iα, where α is the angular acceleration.Bridging: The point particle derivation is recovered when considering only translational motion of the center of mass, ignoring rotation. The extended body derivation shows that the translational motion is decoupled from the rotational motion if the force acts through the center of mass. The full derivation involves integrating over the mass distribution of the body, essentially summing up the contributions of infinitesimal point masses.

Discrete Charges to Continuous Charge Distribution (Electromagnetism):

Simplified Derivation (Discrete Charges):

Coulomb's Law: The force between two point charges q1 and q2 separated by a distance r: F = k * q1 * q2 / r2 .Superposition Principle: The net electric field or force due to multiple point charges is the vector sum of the fields/forces due to each individual charge.

More Realistic Derivation (Continuous Charge Distribution):

Integration: To find the electric field or potential due to a continuous charge distribution (e.g., a charged rod, a charged sphere), you perform an integration over the distribution. You consider an infinitesimal element of charge dq and treat it as a point charge, then integrate its contribution over the entire distribution:

dE = k * dq / r2 * r̂ (electric field element)

V = ∫ k * dq / r (electric potential)

Bridging: If you have a finite number of discrete charges, the integral effectively becomes a sum over those charges. The concept of charge density (charge per unit volume, area, or length) is introduced to transition from discrete to continuous.

Ideal Conductor to Real Conductor (Electromagnetism):

Simplified Derivation (Ideal Conductor):

Ohm's Law (simplified): For an ideal conductor, voltage V is applied, and current I flows with effectively zero resistance, implying infinite current for any non-zero voltage (or zero voltage for any finite current).Circuit Analysis: Ideal conductors simplify circuit analysis, assuming instantaneous propagation of electric fields and no energy loss within the connecting wires.

More Realistic Derivation (Real Conductor):

Ohm's Law (with resistance): V = IR, where R is the resistance of the conductor.Microscopic Model of Conduction: Derives Ohm's law from the drift velocity of electrons in a conductor due to an electric field, considering collisions with the lattice structure that cause resistance. This involves concepts like mean free path and relaxation time.Joule Heating: The derivation naturally leads to the understanding of power dissipation as heat (P = I2 R).Bridging: Setting the resistance R to zero in the more realistic derivation recovers the ideal conductor scenario.

Reversible Process to Irreversible Process (Thermodynamics):

Simplified Derivation (Reversible Process):

Ideal Gas Law and Thermodynamic Equations: Derivations often assume reversible processes for simplicity, allowing for precise calculations of work and heat transfer (e.g., for isothermal or adiabatic reversible processes).Entropy Change: The change in entropy for a reversible process is defined as dS = dQ/T.

More Realistic Derivation (Irreversible Process):

Second Law of Thermodynamics: Explicitly accounts for the increase in entropy in irreversible processes. The entropy change ΔS for an irreversible process is greater than ∫ dQ/T.Examples of Irreversibility: Derivations analyze processes like heat conduction through a temperature difference, friction, and free expansion, showing how they lead to an increase in entropy and are therefore irreversible.Bridging: The reversible process serves as an idealized limit. The derivations for irreversible processes quantify the deviations from this ideal, showing how factors like friction introduce entropy generation.

Flat Spacetime to Curved Spacetime (Relativity):

Simplified Derivation (Flat Spacetime - Special Relativity):

Lorentz Transformations: Describe how space and time coordinates transform between inertial frames in the absence of gravity.Energy-Momentum Relation: E2 = (pc)2 + (mc2 )2 is derived in flat spacetime.

More Realistic Derivation (Curved Spacetime - General Relativity):

Einstein Field Equations: Relate the curvature of spacetime to the distribution of mass and energy. These are highly complex tensor equations.Geodesics: Objects move along geodesics in curved spacetime, which become straight lines in the limit of flat spacetime.Bridging: In regions where gravity is weak and velocities are much less than the speed of light, the solutions to the Einstein field equations approximate the flat spacetime of special relativity. The concept of the metric tensor gμν is introduced, which reduces to the Minkowski metric in flat spacetime.

How These Derivations Span the Assumptions:

In each of these examples, the more "realistic" derivation:

Includes more complexities: Factors like internal structure, resistance, irreversibility, or spacetime curvature are explicitly considered.Introduces new mathematical tools and concepts: Integration, vector calculus, thermodynamics principles, and tensor calculus are employed.Reduces to the simplified case under certain limits or assumptions: By setting parameters to zero, ignoring certain effects, or making approximations, the results of the simplified derivation are recovered.

These derivations are not just about having two separate formulas; they are about understanding the relationship between the simplified model and the more accurate one. The mathematical steps often explicitly show how the simplifying assumptions restrict the more general case. This is a core part of how physics builds upon previous understanding and refines its models of reality.

prompt

Provide an example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of classical mechanics and quantum mechanics.

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: thoughts

Here's a breakdown of the thinking process behind constructing the example of the quantum harmonic oscillator derivation bridging classical and quantum mechanics:

**Identify the Core Dichotomy:** The request asks for a bridge between classical and quantum mechanics. The fundamental difference lies in how these theories describe the behavior of particles – deterministic trajectories vs. probabilistic wave functions.

**Choose a Concrete Example:** A good example needs to be simple enough to illustrate the connection without getting bogged down in advanced mathematics, yet fundamental enough to be meaningful in both frameworks. The **harmonic oscillator** is a perfect choice because:

It's solvable analytically in both classical and quantum mechanics.

It's a ubiquitous model for many physical systems (vibrations, oscillations in fields, etc.).

The classical solution provides a clear picture of deterministic motion.

**Outline the Classical Derivation:**

**Start with Newton's Second Law:** This is the foundation of classical mechanics.

**Apply to the Harmonic Oscillator:** Introduce the restoring force proportional to displacement (`F = -kx`).

**Solve the Differential Equation:** This yields the sinusoidal solution for position as a function of time, demonstrating the deterministic nature of the motion (knowing initial conditions fully determines the future).

**Identify Key Classical Quantities:** Focus on energy, which is a continuous quantity in the classical picture. Express the total energy in terms of position and velocity (or amplitude and angular frequency).

**Outline the Quantum Derivation:**

**Start with the Schrödinger Equation:** This is the fundamental equation of quantum mechanics.

**Apply to the Harmonic Oscillator:** Introduce the potential energy function (`V(x) = 1/2 kx^2`).

**Solve the Schrödinger Equation:** This involves finding the stationary states (energy eigenstates) and their corresponding wave functions. This is where the mathematical complexity increases.

**Key Quantum Concepts:** Emphasize the quantization of energy levels (discrete values), the probabilistic interpretation of the wave function (probability density of finding the particle), and the existence of a zero-point energy.

**Establish the Bridge - The Correspondence Principle:**

**State the Principle:** Explain Bohr's Correspondence Principle – quantum mechanics should reproduce classical results in the limit of large quantum numbers or macroscopic systems.

**Show the Connection through Energy Levels:** Demonstrate that as the quantum number `n` becomes large, the energy difference between adjacent levels becomes much smaller than the energy itself. This makes the energy spectrum appear nearly continuous, approaching the classical picture.

**Show the Connection through Probability Distributions:** Explain that for high quantum numbers, the probability distribution of the particle's position starts to resemble the classical probability of finding the particle at a given location (more likely near the turning points).

**Connect to Classical Frequency:** Highlight that the frequency of transitions between adjacent high-energy levels approaches the classical oscillation frequency.

**Discuss the Role of Planck's Constant:** Emphasize that Planck's constant (`ħ`) is the "bridge" mathematically. It's present in the quantum mechanical description and its small value is why quantum effects are not readily apparent in the macroscopic world. Taking the limit `ħ → 0` (formally) recovers classical mechanics.

**Structure the Explanation:** Organize the answer logically with clear headings and bullet points for readability. Start with the classical derivation, move to the quantum derivation, and then explicitly connect them using the correspondence principle.

**Refine and Clarify:** Review the explanation for clarity, accuracy, and completeness. Ensure that the key differences and connections between the classical and quantum descriptions are clearly articulated. Use simple language where possible while maintaining scientific rigor. For example, instead of just saying "solve the Schrödinger equation," briefly mention what kind of solutions are sought (stationary states, energy eigenstates).

Essentially, the process involves: identifying the core difference, selecting a relevant example, outlining the derivations in each framework, and then explicitly demonstrating how the quantum description reduces to the classical one under appropriate limits, highlighting the key concepts and mathematical tools involved.

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: response

Bridging Classical and Quantum Mechanics: The Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

A compelling example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of classical mechanics and quantum mechanics is the treatment of the harmonic oscillator .

Classical Harmonic Oscillator

Assumptions of Classical Mechanics:

Particles have definite trajectories and properties (position, momentum) at all times.

Energy is a continuous quantity.

Motion is governed by Newton's laws of motion.

Classical Derivation:

Consider a mass m attached to a spring with spring constant k . The restoring force is given by Hooke's Law: F = -kx .

Applying Newton's Second Law (F = ma ):

m d2 x /dt2 = -kx

This is a second-order linear homogeneous differential equation with the general solution:

x(t) = A cos(ωt + φ)

Where:

A is the amplitude of oscillation.ω = √(k/m ) is the angular frequency.

φ is the phase constant.

The total energy of the classical harmonic oscillator is:

E = 1/2 mv 2 + 1/2 kx 2 = 1/2 m ω2 A 2 = 1/2 kA 2

Importantly, in classical mechanics, the energy E can take any continuous value depending on the amplitude A .

Quantum Harmonic Oscillator

Assumptions of Quantum Mechanics:

Particles are described by wave functions, and their properties are probabilistic.

Energy is often quantized, meaning it can only take on discrete values.

Motion is governed by the Schrödinger equation.

Quantum Derivation:

The time-independent Schrödinger equation for a one-dimensional system is:

-ħ2 /2m d2 ψ(x )/dx 2 + V(x) ψ(x ) = E ψ(x )

For the harmonic oscillator, the potential energy is V(x) = 1/2 kx 2 .

Solving this differential equation (which involves techniques like using ladder operators or series solutions) yields the allowed energy levels:

En = (n + 1/2)ħω

Where:

n is a non-negative integer (n = 0, 1, 2, ...), called the quantum number.ħ is the reduced Planck constant.

This result shows that the energy of the quantum harmonic oscillator is quantized ; it can only take on specific discrete values. The lowest energy level, E 0 = 1/2 ħω, is known as the zero-point energy , a purely quantum mechanical phenomenon with no classical counterpart.

Bridging the Assumptions: The Correspondence Principle

The bridge between the classical and quantum descriptions lies in the Correspondence Principle , formulated by Niels Bohr. This principle states that the predictions of quantum mechanics should approach the predictions of classical mechanics in the limit of large quantum numbers or macroscopic systems.

How the Harmonic Oscillator Demonstrates the Correspondence Principle:

High Quantum Numbers (Large n ): As the quantum number n becomes very large, the energy difference between adjacent energy levels, ΔE = E n +1En = ħω, becomes much smaller compared to the energy itself, En ≈ n ħω. In this limit, the energy spectrum appears almost continuous, resembling the classical picture where energy can take any value.Classical Limit (Large Amplitudes/Energies): Consider a macroscopic oscillator with a very large amplitude. The energy of this system will correspond to a very high quantum number n . The quantum jumps between adjacent energy levels are so small relative to the total energy that they become practically imperceptible, and the energy appears continuous.Frequency of Transitions: The frequency of transitions between adjacent energy levels in the quantum oscillator is ΔE /ħ = ω, which is precisely the classical oscillation frequency.

Mathematical Connection:

While the derivations are fundamentally different (classical uses Newton's laws, quantum uses the Schrödinger equation), the **results converge in the appropriate limits**. The classical frequency emerges from the quantum treatment, and the discrete energy levels become effectively continuous at high energies.

Conclusion

The quantum harmonic oscillator provides a beautiful example of how quantum mechanics builds upon and extends classical mechanics. While classical mechanics treats energy as continuous, quantum mechanics reveals its discrete nature. However, the Correspondence Principle ensures that in the appropriate limits, the quantum description seamlessly transitions to the familiar classical behavior. This highlights the power of physical theories to provide accurate descriptions across different scales and regimes.

prompt

Provide an example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of classical mechanics and electromagnetics. Format your response as HTML rather than markdown.

Note: hyperlinks below added outside the LLM as part of my validation the words are not being hallucinated.

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: response

Bridging Classical Mechanics and Electromagnetism: Radiation from an Accelerating Charge

One significant example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of classical mechanics and electromagnetism is the calculation of electromagnetic radiation emitted by an accelerating charged particle . This derivation beautifully combines concepts from both domains.

Classical Mechanics Perspective

Assumptions:

Particles have definite trajectories and are described by their position, velocity, and acceleration as functions of time.

Newton's laws of motion govern the particle's movement under the influence of forces.

Input from Mechanics:

We start by considering a single point charge q undergoing acceleration a (t ). The exact form of the acceleration depends on the forces acting on the charge, which are governed by classical mechanics (e.g., a charge moving in a circle experiences centripetal acceleration).

Classical Electromagnetism Perspective

Assumptions:

Electric and magnetic fields are continuous entities described by Maxwell's equations.

Accelerating charges produce electromagnetic waves that propagate through space.

These waves carry energy and momentum.

Derivation Steps:

Liénard-Wiechert Potentials :A ) generated by a moving point charge. These are given by the Liénard-Wiechert potentials, which are retarded potentials accounting for the finite speed of light:

φ(r , t ) = \frac{1}{4πε0 } qc }{(rc - r · v )}ret

A (r , t ) = \frac{μ0 qc }{4π} v }{(rc - r · v )}ret

Where:

r is the vector from the retarded position of the charge to the observation point.v is the velocity of the charge at the retarded time.The subscript 'ret' indicates that these quantities are evaluated at the retarded time t' , such that t - t' = |r - r '(t' )|/c .

Calculating Electric and Magnetic Fields: The electric field E and magnetic field B are derived from the potentials using:

E = -∇φ - ∂A /∂t

B = ∇ × A

These calculations are lengthy and involve careful differentiation, especially considering the dependence on the retarded time.

Separating Velocity and Acceleration Fields: The resulting electric and magnetic fields can be separated into two parts: velocity fields (which dominate at short distances and are related to the Coulomb field) and acceleration fields (which dominate at large distances and constitute the radiation). The acceleration fields are proportional to the acceleration of the charge.Poynting Vector and Power Radiated: The power radiated per unit area is given by the Poynting vector:

S = &frac{1}{μ0 } E × B

For the radiation fields, the Poynting vector points radially outward, indicating energy flow away from the charge.

Larmor's Formula: Integrating the Poynting vector over a closed surface far from the charge yields the total power radiated. For a non-relativistic accelerating charge (v << c ), this leads to Larmor's Formula :

P = &frac{μ0 q 2 a 2 }{6πc }

Where a is the magnitude of the acceleration.

Relativistic Generalization (Liénard's Formula): For relativistic accelerations, the formula becomes more complex (Liénard's generalization):

P = &frac{μ0 q 2 }{6πc } γ6 ( |a |2 - |v × a /c |2 )

Where γ is the Lorentz factor.

Bridging the Assumptions

Mechanics Provides the Source: The derivation crucially relies on the mechanical motion of the charged particle, specifically its acceleration a (t ), which is determined by classical mechanics. Without knowing the acceleration, we cannot calculate the radiated power.Electromagnetism Describes the Radiation: Maxwell's equations and the concept of electromagnetic fields are essential for describing how the acceleration of the charge generates and propagates electromagnetic waves carrying energy.Interdependence: The emitted radiation, in turn, can exert a force on the charged particle (radiation reaction), influencing its subsequent mechanical motion. This creates a feedback loop between the two domains.Limits and Approximations: Larmor's formula is a non-relativistic approximation, valid when the speed of the charge is much less than the speed of light. The full derivation using Liénard-Wiechert potentials handles relativistic speeds.

Conclusion

The derivation of the radiation emitted by an accelerating charge is a prime example of how classical mechanics and electromagnetism are intertwined. Classical mechanics provides the description of the source (the accelerating charge), while classical electromagnetism describes the resulting fields and radiation. This derivation is fundamental in understanding phenomena like radio wave emission from antennas, synchrotron radiation, and bremsstrahlung (braking radiation).

prompt

Provide an example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of classical mechanics and relativity.

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: response

Bridging Classical Mechanics and Relativity: Relativistic Momentum

A fundamental example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of classical mechanics and special relativity is the derivation of the expression for relativistic momentum .

Classical Mechanics Perspective (Failure at High Speeds)

Assumptions:

Time is absolute and the same for all observers.

Mass is a constant property of an object, independent of its velocity.

Momentum is defined as p = m v .

Velocities add linearly (Galilean transformations).

The Problem with Classical Momentum:

Classical mechanics works very well for everyday speeds. However, when dealing with speeds approaching the speed of light, it leads to inconsistencies with experimental observations and the principle of relativity (that the laws of physics are the same for all inertial observers).

One crucial issue arises when considering collisions and the conservation of momentum in different inertial frames. If classical momentum is used with Galilean transformations, momentum is not conserved in all inertial frames at relativistic speeds.

Special Relativity Perspective

Assumptions:

The laws of physics are the same for all inertial observers.

The speed of light in a vacuum (c ) is constant for all inertial observers, regardless of the motion of the source of light.

Time and space are relative and linked through the Lorentz transformations.

Energy and momentum are related and form a four-vector.

Derivation of Relativistic Momentum:

The derivation of relativistic momentum typically involves considering a thought experiment involving an inelastic collision between two identical objects as observed from two different inertial frames of reference. The key is to uphold the principle of conservation of momentum in all inertial frames, a cornerstone of physics.

Consider Two Inertial Frames : Frame S and Frame S', where S' moves with a constant velocity v along the x-axis relative to S.The Collision : In Frame S', two identical objects A and B have equal and opposite velocities along the y'-axis before colliding inelastically. After the collision, they stick together and are at rest in S'.Observations in Frame S : Using the velocity addition formulas from special relativity (derived from Lorentz transformations), we determine the velocities of objects A and B in Frame S before the collision. These velocities will have both x and y components.Classical Momentum Conservation (Fails) : If we apply classical momentum conservation in Frame S, we find that momentum is NOT conserved along the y-axis. This indicates that the classical definition of momentum is inadequate at relativistic speeds.Seeking a Modified Momentum : To preserve the law of conservation of momentum in all inertial frames, we need to modify the definition of momentum. We hypothesize a velocity-dependent factor, γ(u ), multiplying the classical momentum, where u is the speed of the object in the given frame. So, the relativistic momentum is proposed to be p = m γ(u ) u .Applying Relativistic Velocity Addition : Using the relativistic velocity addition formulas to transform velocities between the frames and enforcing momentum conservation in both frames allows us to solve for the form of γ(u ).The Lorentz Factor : Through this process, it is found that the velocity-dependent factor must be the Lorentz factor:

γ(u ) = \frac{1}{√(1 - u 2 /c 2 )}

Relativistic Momentum Formula : Therefore, the expression for relativistic momentum is:

p = γ(u ) m u = \frac{m u }{√(1 - u 2 /c 2 )}

Bridging the Assumptions

Classical Limit : At low speeds (u << c ), the Lorentz factor γ(u ) approaches 1. In this limit, the relativistic momentum reduces to the classical momentum p = m u . This shows that classical mechanics is a valid approximation at low speeds.Conservation Laws : The derivation hinges on the fundamental principle of conservation of momentum, a cornerstone of classical mechanics, but extends it to be consistent with the principles of special relativity.Relativity Modifies Classical Concepts : Relativity doesn't discard classical mechanics entirely but rather shows that concepts like momentum (and also mass and energy, as seen in the famous E=mc²) need to be modified at high speeds to be consistent with the fundamental postulates of relativity.Lorentz Transformations are Crucial : The velocity addition formulas derived from the Lorentz transformations are essential for relating the observations in different inertial frames and for deriving the correct form of relativistic momentum.

Conclusion

The derivation of relativistic momentum is a prime example of how special relativity builds upon and refines classical mechanics. It demonstrates that classical mechanics is a limiting case of relativistic mechanics at low speeds. By upholding fundamental principles like the conservation of momentum and incorporating the postulates of special relativity, we arrive at a more accurate description of motion at all speeds.

prompt

Provide an example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of quantum mechanics and electromagnetics. Format your response as HTML rather than markdown.

2025-01-20: Gemini 2.0 Flash Thinking Experimental: response

Bridging Quantum Mechanics and Electromagnetism: Spontaneous Emission

A cornerstone example of a derivation that bridges the assumptions of quantum mechanics and electromagnetism is the calculation of the rate of spontaneous emission of a photon by an excited atom.

Quantum Mechanics Perspective (Atom)

Assumptions:

The atom's electrons exist in discrete energy levels.

Transitions between these energy levels involve the absorption or emission of photons.

The state of the atom is described by a wavefunction that evolves according to the time-dependent Schrödinger equation.

Quantum Mechanical Description of the Atom:

Consider an atom with an electron in an excited state |e ⟩ with energy Ee . There is a lower energy state |g ⟩ (ground state) with energy Eg . In the absence of external fields, the atom can spontaneously transition from the excited state to the ground state.

Classical Electromagnetism Perspective (Radiation Field - Initially Simplified)

Initial Simplified Assumption:

Initially, when first approaching this problem, one might consider a simplified classical picture of the electromagnetic field, perhaps just thinking about the energy difference being released as a classical wave. However, a purely classical treatment fails to explain the discrete nature of photon emission and the concept of spontaneous emission.

Quantum Electrodynamics (QED) Perspective - The Bridge

Assumptions of Quantum Electrodynamics:

The electromagnetic field is quantized, meaning it consists of photons, which are the quanta of the electromagnetic field.

The interaction between the atom and the electromagnetic field is described by quantum mechanical perturbation theory.

Even in a vacuum, there exist quantum fluctuations of the electromagnetic field (zero-point energy).

Derivation Steps:

Quantization of the Electromagnetic Field: The classical electromagnetic field is treated as a collection of quantum harmonic oscillators, one for each mode (frequency and polarization) of the field. The energy of each mode is quantized in units of ħω. Even the vacuum state has a non-zero energy (zero-point energy).Interaction Hamiltonian:** The interaction between the atom's electrons and the quantized electromagnetic field is described by an interaction Hamiltonian, which is proportional to the dot product of the atom's dipole moment operator (d ) and the electric field operator (E ).

H int = - d · E

Time-Dependent Perturbation Theory: Since the interaction is relatively weak, we use time-dependent perturbation theory to calculate the transition rate from the initial state (excited atom, no photons in the relevant mode) to the final state (ground state atom, one photon emitted into a specific mode).Fermi's Golden Rule: Fermi's Golden Rule provides the transition rate (probability per unit time) for transitions between quantum states due to a perturbation:

Γe →g f |H int |i ⟩|2 ρ(Ef )

Where:

|i ⟩ is the initial state (excited atom, vacuum field).

|f ⟩ is the final state (ground state atom, one photon).

ρ(Ef ) is the density of final states (number of photon modes per unit energy around the emitted photon's energy).

Calculating the Matrix Element: The matrix element ⟨f |H int |i ⟩ involves the expectation value of the interaction Hamiltonian between the initial and final states. This involves the dipole moment operator of the atom and the creation and annihilation operators for photons in the electromagnetic field.Summing over Photon Modes: Since the photon can be emitted in any direction and polarization, we need to sum (or integrate) over all possible modes of the emitted photon. This is where the density of states ρ(Ef ) comes in.Spontaneous Emission Rate: The final result for the spontaneous emission rate (Einstein A coefficient) is:

A 21 = \frac{ω3 |d eg |2 }{3π ε0 ħ c 3 }

Where:

ω = (Ee - Eg )/ħ is the angular frequency of the emitted photon.

d eg = ⟨g |d |e ⟩ is the transition dipole moment.

Bridging the Assumptions

Quantum Atom, Quantum Field: The derivation explicitly treats both the atom and the electromagnetic field quantum mechanically. The discrete energy levels of the atom and the quantized nature of light (photons) are fundamental.Interaction is Key: The interaction Hamiltonian describes how the quantum states of the atom and the electromagnetic field are coupled, allowing for energy transfer in the form of photon emission.Spontaneous Emission Explained: The concept of spontaneous emission arises naturally from the interaction with the vacuum fluctuations of the quantized electromagnetic field. Even in the absence of external light, the atom interacts with these zero-point fluctuations, causing it to decay to a lower energy state by emitting a photon. This is a purely quantum electrodynamical effect with no classical analog.Perturbation Theory as an Approximation: The use of perturbation theory assumes a weak interaction between the atom and the field. For strong fields, more advanced QED techniques are needed.

Conclusion

The derivation of the spontaneous emission rate is a triumph of quantum electrodynamics, demonstrating how the quantization of both matter and the electromagnetic field leads to phenomena that cannot be explained by classical physics alone. It beautifully bridges the gap between the quantum mechanical description of atoms and the quantum mechanical description of light, providing a fundamental understanding of how atoms emit light.

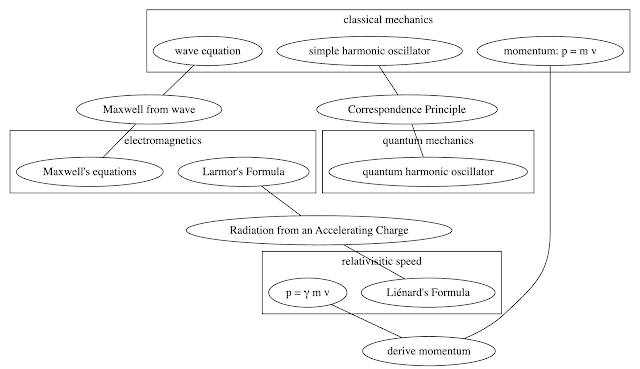

So that set of LLM ideation provides a map that spans topics:

https://dreampuf.github.io/GraphvizOnline/

graph G {

subgraph cluster_classical_mechanics {

label="classical mechanics";

wave_equation [label="wave equation"];

classical_momentum [label="momentum: p = m v"];

simple_harmonic_oscillator [label="simple harmonic oscillator"];

};

subgraph cluster_quantum_mechanics {

label="quantum mechanics";

quantum_harmonic_oscillator [label="quantum harmonic oscillator"];

};

correspondence_principle [label="Correspondence Principle"];

simple_harmonic_oscillator -- correspondence_principle;

correspondence_principle -- quantum_harmonic_oscillator;

subgraph cluster_electromagnetics {

label="electromagnetics";

maxwells_equations [label="Maxwell's equations"];

larmors_formula [label="Larmor's Formula"];

};

derive_maxwell_from_wave [label="Maxwell from wave"];

wave_equation -- derive_maxwell_from_wave;

derive_maxwell_from_wave -- maxwells_equations;

subgraph cluster_relativistic_speed {

label = "relativisitic speed";

relativistic_momentum [label="p = γ m v"];

lienards_formula [label="Liénard's Formula"];

}

radiation_accelerating_charge [label="Radiation from an Accelerating Charge"];

larmors_formula -- radiation_accelerating_charge;

radiation_accelerating_charge -- lienards_formula;

derive_momentum [label="derive momentum"];

relativistic_momentum -- derive_momentum;

derive_momentum -- classical_momentum;

}

Rendered in 0.002 seconds using Flask